GENEVA (Switzerland)- Tracking silky sharks has revealed them to be swift swimmers. But they’re also one of the most heavily fished sharks globally. Will expanded marine protection in the Tropical Eastern Pacific go far enough to protect these long-distance swimmers?

Smooth, slender and swift. Enter the silky shark, one of the ocean’s most inquisitive predators. Silky sharks are true travelers, roaming open seas and diving to depths of more than 300 metres (985 feet). Yet their tendency to feed on schools of tuna and to spend most of their time in relatively shallow waters (less than 100 metres, or 328 feet, deep) renders them extremely vulnerable to industrial fishing.

Migration patterns

Since 2014 the Save Our Seas Foundation Shark Research Center (SOSF-SRC) and the Guy Harvey Research Institute (GHRI) at Nova Southeastern University (NSU) in Florida, USA, have been working jointly to discover more about the migration patterns of silky and other open-ocean sharks globally. By uncovering where and when the sharks spend their time, knowledge generated can better inform conservation plans and management actions needed to protect the animals during their travels. During 2021, in a research partnership between the Charles Darwin Foundation (CDF) and the Galápagos National Park Directorate, researchers expanded silky shark satellite tagging to include the iconic Galápagos Marine Reserve.

Dr. Pelayo Salinas de León, senior marine ecologist at the CDF and a 2021 SOSF Fellowship Grantee, oversees this tagging work in his ‘office’ – the Galápagos Islands. Darwin’s living laboratory is home to large shivers of scalloped hammerhead sharks, huge whale sharks and the curious tiger shark. This shark sanctuary supports the largest shark biomass reported on any reef in the world and the silky shark is one of the dominant pelagic species here.

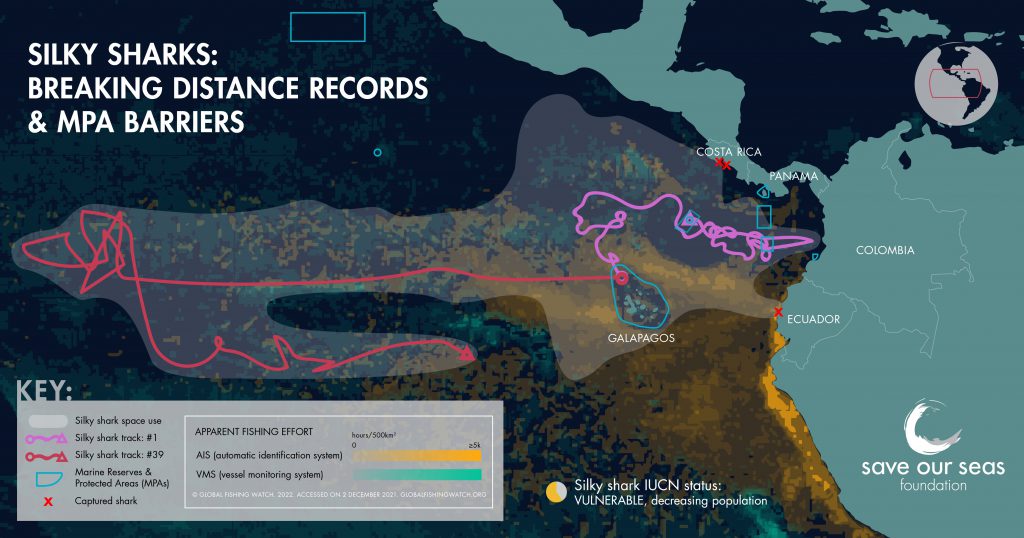

So, what have we learned after the tagging of 47 adult silky sharks during 2021? The distances they swim are massive! One female shark (Silky 1) traveled nearly 7,000 kilometres (4,350 miles) in seven months between February and September 2021, visiting the UNESCO World Heritage Sites and marine protected areas of Galápagos, Isla del Coco and Malpelo along the way. But she also spent most of that time in unprotected areas in a region where there are high levels of illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing.

The silky shark tracks can be followed on the Guy Harvey Research Institute website (select project 22) https://ghriresearch.org/

Another female shark (Silky 39), tagged on 17 July 2021, took gold for the furthest distance traveled between locations: more than 16,300 kilometres (10,100 miles) in ten months. That distance is more than three times the previous record for this species – and this shark is still being tracked!

Shark fins

But it’s not just their swimming that sets records. Silky shark fins make up the second-highest proportion of fins found in the global market. Fins from up to two million silky sharks contribute to the global fin trade each year. The extremely high fishing pressure these sharks are facing causes dramatic population declines and has resulted in their recent uplisting to Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.

There is hope for silkies and other sharks, though. At COP26 in Glasgow 2021, the presidents of Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, and Panama signed a declaration to establish a new ‘marine corridor’ in the Eastern Tropical Pacific that expands protection and links existing marine protected areas (MPA) to stretch over 500,000 square kilometres (193,000 square miles), an area the size of Spain. This expanded marine protected area could increase protection for sharks on a critical marine migratory route. But does it go far enough to protect sharks that we now know travel much further than previously thought?

Of course, expanding marine protection across the Tropical Eastern Pacific is a great step. It will help to protect the sharks during some of their travels, but silkies don’t know where these MPA lines on a map are, and frequently adventure to adjacent areas open to fishing. And even an MPA isn’t completely safe, since illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing of sharks across the ETP continues to be an issue. MPAs need to be complemented by an urgently needed, ambitious, and comprehensive management plan for silky shark populations across the ETP.

The SOSF-SRC is on a mission to understand the world’s sharks and rays. For the founder of the Save Our Seas Foundation, His Excellency Abdulmohsen Abdulmalik Al-Sheikh, it all began with silky sharks. ‘My love for sharks started with silky sharks,’ he explains. ‘Their tremendous migrations continue to amaze and inspire me. I hope that learning more about where they go, and when and why, can really help us target how best to protect them.’

More on the website of Save Our Seas.